Resources

Genetics 101

All cancer is genetic, caused by changes in genes, often occurring sporadically due to chance or age. However, some individuals inherit a genetic susceptibility that increases their risk of certain cancers.

What are genes?

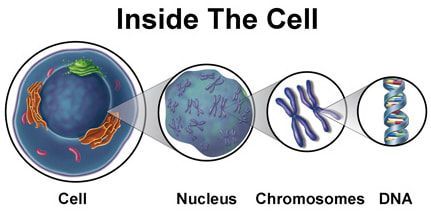

Genes are tiny instruction manuals inside each cell, guiding how the body grows, functions, and repairs itself. Genes are passed down from parents to their children, which is one reason why certain traits — and sometimes health risks — can run in families.

Genes, located in chromosomes within the cell nucleus, are present in every body cell. We have 46 chromosomes in 23 pairs, with one from each parent. Each chromosome contains thousands of genes, which are coded DNA segments that come in pairs. DNA carries instructions for bodily functions, and changes in its sequence can cause genes to malfunction.

Genes and cancer

Variants in genes can influence how those instructions work. Most variants are harmless, but some, known as pathogenic variants, can increase the likelihood of certain diseases, including cancer.

Some pathogenic variants for example can make it harder for cells to repair damage in the cell. Over time, this can allow cancer to develop more easily.

Having a “changed” or “faulty” gene does not mean cancer is present; it simply means the risk is higher. Understanding these changes allows for informed choices about screening, prevention, and care.

Why 'variant' rather than 'mutation'?

The word variant is now preferred term instead of mutation because not all genetic changes are harmful. Variant simply means a difference. This language better reflects the range of changes that can occur — from harmless to harmful — and avoids the negative connotations that 'mutation' can carry.

What are BRCA1 and BRCA2?

These genes were discovered in 1994-1995. The acronym BRCA comes from BReast CAncer 1 or BReast CAncer 2.

Normally these genes act like brakes that help stop abnormal cell growth. However, if a woman has inherited a variation in one of these genes, she has a higher chance of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer than a woman with a well-functioning gene. A man with an inherited BRCA variation also has an increased risk of breast cancer compared to the general population, as is his risk of prostate cancer.

About 1 in every 500 – 1000 people carry a pathogenic variant in BRCA1 or BRCA2. It is important to know that the majority of breast cancer is not due to an inherited faulty gene.

Understanding hereditary breast and ovarian cancer

A family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer is an important risk factor. A family history means having one or more blood relatives on the same side of the family diagnosed with breast and or ovarian cancer. These relatives could be on your mother’s or father’s side of the family. BRCA genes are inherited equally by males and females.

Since breast cancer is common, a family history of breast cancer can also be due to chance and age. This is why a detailed look at the family history is so important.

A parent with a pathogenic variant in BRCA1 or BRCA2 has a 1 in 2 chance (50%) of passing it onto each child they have. That means that there is also a 50% chance for each individual child to inherit a normal BRCA gene from their parent. If the normal gene is inherited, the risk for breast or ovarian cancer is the same as in the general population.

Remember, cancer is not inherited, only the gene variant that increases the risk of developing it.

What are the risks associated with a variant in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene?

In the general population about 1 in 8 to 1 in 9 women will develop breast cancer in their lifetime, and 1 in 100 women will develop ovarian cancer. The majority of women who get breast or ovarian cancer do not carry a BRCA variant.

Women with a variant in the BRCA gene are at increased risk for cancer of the breast and ovary. Women with a BRCA mutation have about a 70% risk of developing breast cancer by the age of 90, and a risk of ovarian cancer of 44% with BRCA1 or 17% with BRCA2. So not all women who have inherited a BRCA variant will develop breast or ovarian cancer, but the risks are much higher.

A woman who carries a BRCA variant has an increased risk of developing another primary breast cancer in their breast.

A man who carries a BRCA variant has a risk of breast cancer by the age of 80 of 0.4% with BRCA1 and 3.8% BRCA2, and his risk of prostate cancer is also increased.

The risk for pancreatic, bile duct, and melanoma cancers also appear to be slightly increased in individuals with a BRCA mutation.

How do I know if I have a genetic variant (mutation)?

If you have a strong family history, it may be appropriate for your General Practitioner to refer you to Genetic Health Service New Zealand.

The family history could include:

- more than one cancer (that is, two separate breast cancers or a breast and ovarian cancer)

- multiple relatives with breast and/or ovarian cancer

- triple negative breast cancer

- young diagnosis of breast cancer (40 years or younger).

There is a higher incidence of BRCA variants in people with Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish ancestry.

We advise you to learn about your family history and take that with you to discuss with your GP.

What will a referral to Genetic Services involve?

The risk of breast or ovarian cancer based on family history will be calculated and discussed, along with appropriate surveillance and management options. The limitations and benefits of genetic testing will also be reviewed, including possible arrangements for testing.

Testing for a BRCA variant should start with a family member who has breast cancer to improve detection rates. Over 3,000 unique mutations have been identified. If a variant is found, testing can be offered to at-risk adult family members (aged 18 or over).

Genetic testing applies to only a small percentage of breast cancer cases, with at least 95% not linked to BRCA mutations.